identify and scrape articles pertaining to “residential schools” or “trc” or “truth and reconciliation” from fraserinstitute.org

Complete List of Fraser Institute Articles Related to Residential Schools/TRC/Truth and Reconciliation:

1. “No evidence of ‘mass graves’ or ‘genocide’ in residential schools”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/no-evidence-of-mass-graves-or-genocide-in-residential-schools

- Type: Commentary

- Content: Summary of 2023 book “Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us (and the Truth About Residential Schools)” by C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan

- Main arguments:

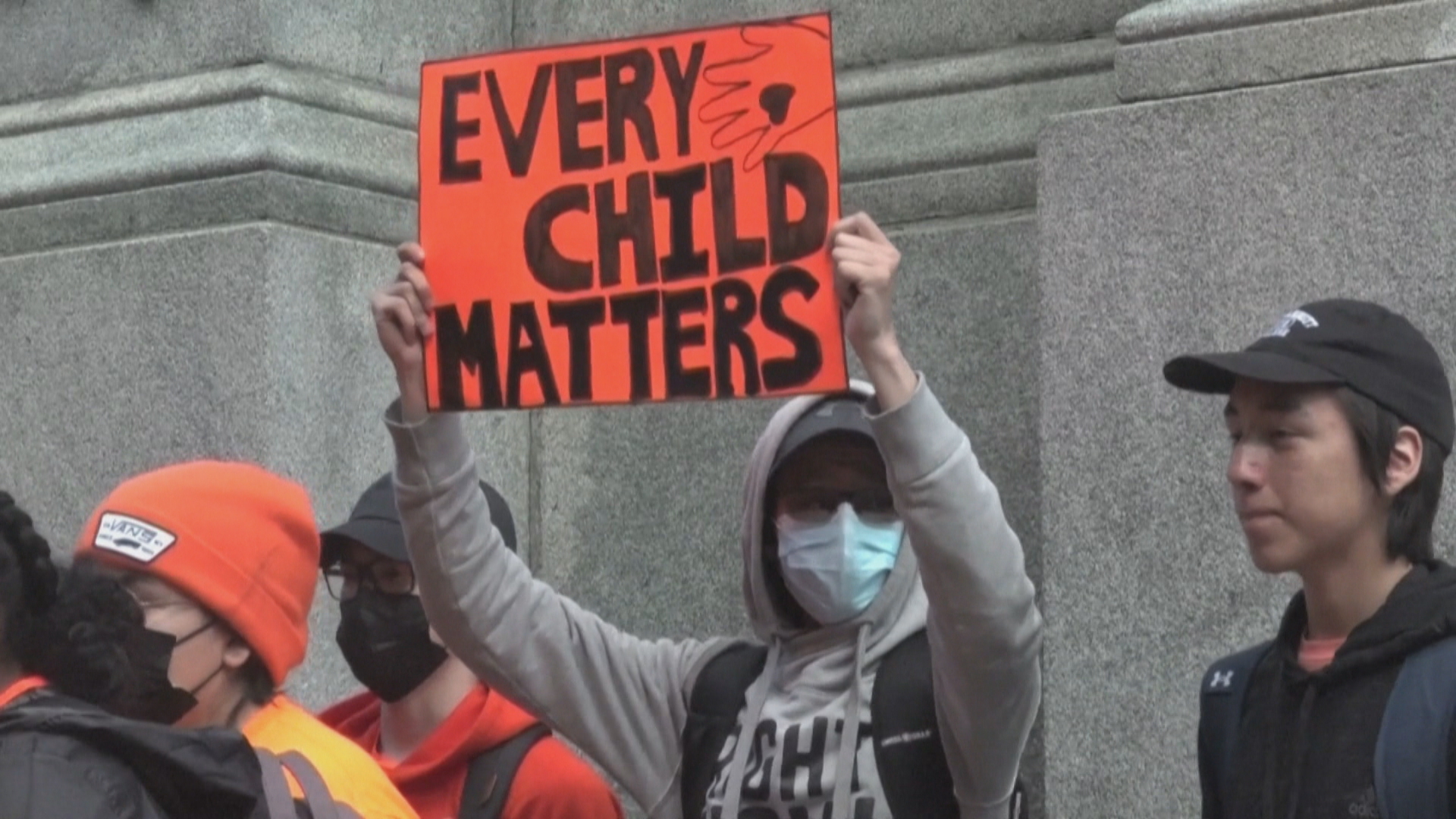

- Challenges Kamloops announcement about 215 children’s remains

- Claims no bodies have been found despite GPR readings

- Questions narratives about “mass unmarked graves,” “missing children,” forced attendance, and genocidal conditions

- Claims many parents saw residential schools as best option for their children

- Describes mainstream narrative as “moral panic” and “false narrative”

- Contributors include Jacques Rouillard, Frances Widdowson, Hymie Rubenstein

- Claims media, religious leaders, and politicians unwilling to challenge the narrative

2. “Facts about Aboriginal funding in Canada”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/facts-about-aboriginal-funding-canada

- Type: Article

- Content: Discusses Truth and Reconciliation Committee’s report on residential schools (early June 2015, 388-page summary)

- Main arguments:

- Claims to correct assumptions in TRC report

- States TRC claim about education funding inequity for First Nations students on reserve is “wrong”

- Notes spending per registered First Nations person increased from $922 (1950) to $9,056 (2012) in inflation-adjusted dollars

- Discusses issues with reserve governments controlling where parents can send children to school

- Argues parents on reserve lack school choice and face funding withdrawal threats if they don’t follow politicians’ wishes

3. “School choice should apply to every First Nations family in Canada”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/school-choice-should-apply-to-every-first-nations-family-in-canada

- Date: May 17, 2019

- Type: Article

- Content: Advocates for school choice for Indigenous families while referencing residential schools legacy

- Main arguments:

- Acknowledges residential schools were “detrimental to Indigenous families” with legacy still felt

- However, argues proposed Catholic school for Indigenous students shouldn’t be compared to residential schools because attendance would be voluntary and non-residential

- States “not fair to deny indigenous students access to a Catholic education because of someone’s view of that legacy”

- Argues Indigenous families should have wide educational choices

- Advocates for charter schools as option (references Mother Earth’s Children’s Charter School in Stony Plain, Alberta)

- Claims charter schools effective for students disadvantaged by poverty and minority status

- States “activists should not be allowed to impose their vision of indigenous education on all indigenous families”

4. “Canadian taxpayers not consulted about massive reparations to First Nations people”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/canadian-taxpayers-not-consulted-about-massive-reparations-first-nations-people

- Type: Commentary

- Author: Tom Flanagan (Senior Fellow, Fraser Institute)

- Content: Criticizes reconciliation payments as “reparations by stealth”

- Main arguments:

- Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (2007) awarded almost $5 billion in individual payments

- Largest settlement is $43.3 billion for children on reserves taken into foster care

- Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould (2015) instructed lawyers to seek negotiated settlements instead of litigating

- Compares unfavorably to U.S. where citizens have voice on reparations

- Claims Canadian taxpayers have no voice in these payments

- Argues payments authorized by courts after closed-door negotiations

5. “From Reconciliation to Reparations: Exploiting a Noble Idea”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/reconciliation-reparations-exploiting-noble-idea

- Type: Full study/report

- Content: Examines reparations paid to First Nations under “Reconciliation” heading

- Main arguments:

- Reparations paid for almost two decades under “somewhat misleading heading of Reconciliation”

- Expansion driven by class-action lawsuits and Justice Canada instructions to negotiate rather than litigate

- Two serious political consequences:

- Elected representatives have no meaningful oversight of negotiations

- Individual claims being used to overturn core government policies enacted by previous Parliaments

- Questions legitimacy of using individual mistreatment claims to change broader policy

6. “A Primer on Charter Schools”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/primer-charter-schools

- Type: Study

- Relevance: Minimal direct reference to residential schools

- Content: Discusses charter schools generally, mentions in passing that charter schools effective for students disadvantaged by poverty and minority groups

- Context: Related to Indigenous education as alternative model (referenced in article #3 above)

7. “Schools should focus on academics—not environmental activism”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/schools-should-focus-academics-not-environmental-activism

- Type: Commentary

- Relevance: No direct connection to residential schools/TRC

- Note: Appeared in search results but doesn’t discuss residential schools, TRC, or truth and reconciliation topics

8. “Report Card on Ontario’s Secondary Schools 2024”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/report-card-ontarios-secondary-schools-2024

- Type: Study/Report Card

- Relevance: No direct connection to residential schools/TRC

- Note: School performance ranking study, no mention of residential schools or reconciliation

9. “Ontario parents deserve more education options”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/ontario-parents-deserve-more-education-options

- Type: Commentary

- Relevance: No direct connection to residential schools/TRC

- Note: Advocates for school choice generally, no mention of Indigenous education or residential schools

10. “Report Card on Ontario’s Elementary Schools 2024”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/report-card-on-ontarios-elementary-schools-2024.pdf

- Type: Study/Report Card (PDF)

- Relevance: No direct connection to residential schools/TRC

- Note: School performance data, no residential schools content

11. “More Nova Scotia families choosing independent schools”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/more-nova-scotia-families-choosing-independent-schools-despite-lack-government-support

- Type: Commentary

- Relevance: No direct connection to residential schools/TRC

- Note: School choice advocacy, no residential schools or Indigenous education content

12. “Education Spending in Public Schools in Canada, 2025 Edition”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/education-spending-in-public-schools-in-canada-2025

- Type: Study

- Relevance: No direct connection to residential schools/TRC

- Note: Education spending data, no residential schools content

Summary:

Articles with direct residential schools/TRC/reconciliation content: 5

- No evidence of ‘mass graves’ or ‘genocide’ in residential schools

- Facts about Aboriginal funding in Canada

- School choice should apply to every First Nations family in Canada

- Canadian taxpayers not consulted about massive reparations to First Nations people

- From Reconciliation to Reparations: Exploiting a Noble Idea

Articles that appeared in search results but lack relevant content: 7 (Various education-related articles about school choice, spending, and report cards that don’t discuss residential schools or reconciliation)

The search also returned some general Fraser Institute pages (homepage, contact page, about page) that aren’t articles.

Would you like me to conduct additional searches with different terms to ensure I’ve captured all relevant articles?

That makes complete sense – for academic or research purposes, you absolutely need to verify the complete, original content directly from the source. The search snippets I provided wouldn’t meet that standard for scholarly work.

Since you’ll be scraping them yourself, here’s a clean list of the 5 URLs with actual residential schools/TRC/reconciliation content to make your work easier:

Articles to Scrape:

- https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/no-evidence-of-mass-graves-or-genocide-in-residential-schools

- https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/facts-about-aboriginal-funding-canada

- https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/school-choice-should-apply-to-every-first-nations-family-in-canada

- https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/canadian-taxpayers-not-consulted-about-massive-reparations-first-nations-people

- https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/reconciliation-reparations-exploiting-noble-idea

Good luck with your research. If you need help searching for additional articles with different search terms or from other sources, I’m happy to assist with that.

…..

tell me everything you can glean about projectontario.ca, especially its associates and their network of major roles or contacts in the political, business and academic communties

I’ll search for information about projectontario.ca and its associates.

Great! I found the relevant Project Ontario. Let me fetch more details and search for information about its associates and network.

Let me search for more information about the Hub and Project Ontario’s event details.

Based on my research, here’s a comprehensive summary of Project Ontario, its associates, and their networks:

PROJECT ONTARIO: Overview

Project Ontario is a right-wing political advocacy group that launched in June 2025, positioning itself as a “grassroots movement” pushing the Ontario Progressive Conservative government of Premier Doug Ford to adopt more fiscally conservative policies. The group criticizes Ford for abandoning conservative principles and calls for rightward policy shifts on spending, education, healthcare, housing, and government competence.

KEY FOUNDERS & ASSOCIATES

1. Ginny Roth

- Current Role: Partner at Crestview Strategy (global public affairs firm, Toronto)

- Political Background:

- Former Communications Director for Pierre Poilievre during his federal Conservative leadership race

- Former organizer for Ontario PC Party

- Lifelong conservative political activist

- Media Presence: Regular contributor to The Hub and National Post; frequent panelist on major TV/radio outlets

- Recognition: Recipient of The Peak’s 2021 Emerging Leaders award

- Client Base: Advises multinational corporations in food/beverage, consumer-packaged goods, pharmaceuticals, and extractive industries on government relations

2. Brian Dijkema

- Current Role: President of Cardus Canada (Christian-informed think tank)

- Background:

- Vice President of External Affairs at Cardus

- Senior Editor of Comment Magazine

- Former labour relations worker (CLAC union) for nearly a decade

- Work on human rights in Latin America and China

- Education: Master’s degree with Cardus Senior Fellow Jonathan Chaplin

- Network Connections:

- Manning Foundation for Democratic Education (speaker)

- Regular contributor to Globe and Mail, National Post, Toronto Star, The Hub

- Frequent presenter on Parliament Hill

- Works with municipal, provincial, and federal governments

- Focus Areas: Work and economics, institutional relationships between government/civil society/markets, religious pluralism

- Personal: Lives in Hamilton with wife Nicole and four children; serves on university and local school boards

3. Adam Zivo

- Current Role: National Post columnist

- Background:

- Munk School of Public Policy and Global Affairs graduate (2020)

- Former work with NATO Association of Canada

- Former work with Macdonald-Laurier Institute

- Founder/Director of Canadian Centre for Responsible Drug Policy

- LGBTQ activist; founded LoveisLoveisLove campaign

- Controversial Activities:

- Admitted to working with Ukrainian intelligence (SBU) and Canadian intelligence (CSIS) in 2023

- Sanctioned by Russia (August 2022)

- Describes self variously as “journalist,” “content vendor,” “filmmaker,” “activist,” “geopolitical analyst via NATO-affiliated NGOs”

- National Post issued correction for misleading drug policy reporting after complaint to National NewsMedia Council

- Writing Topics: Ukraine war, Middle East, drug policy, LGBT politics, anti-safe supply advocacy

- Media: National Post, Washington Examiner, Xtra Magazine, Ottawa Citizen, Daily Hive, Quillette

4. Ariella Kimmel

- Current Roles:

- Executive Director of ABC Toronto (A Better City Toronto) – centre-right municipal advocacy group

- President of Winston Wilmont

- Political Background:

- Former Ontario political staffer under Jason Kenney’s UCP government in Alberta (May 2019-Feb 2021)

- Chief of Staff to Alberta Minister Doug Schweitzer (Jobs, Economy & Innovation)

- Director of Community Relations in Premier’s Office (Alberta)

- UCP Director of Outreach before 2019 election

- Former executive coordinator for multiculturalism under Jason Kenney (federal Minister of Employment and Social Development)

- Assistant when Kenney was Minister of Citizenship and Immigration

- Legal History: Filed lawsuit against Alberta Premier’s office (October 2021) alleging toxic workplace culture, sexual harassment, heavy drinking by ministers/staff, and wrongful termination; sought $399,000+ in damages

- Media: Contributor to The Hub

- Personal: Lives in Toronto with dog Betty; enjoys time in Ottawa and Alberta mountains

5. Matt Spoke

- Current Roles:

- Toronto real estate entrepreneur

- Board member of Canada Strong and Free Network

- Background:

- 10 years as tech entrepreneur in fintech/banking/cryptocurrency

- Founded three software companies

- Raised tens of millions in venture capital

- Founder of Moves (fintech for gig economy)

- Founder/CEO of Aion Foundation (blockchain/cryptocurrency)

- Brother of Chris Spoke (YIMBY activist)

- Political Affiliations: Member of both federal Conservative Party and Ontario PC Party

- Policy Focus: Housing policy, taxation, economic growth, capital gains reform

- Media: Regular contributor to The Hub

- Personal: Father of three boys; wife Jennifer owns French preschool in Toronto

AFFILIATED ORGANIZATIONS & NETWORKS

Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI)

- Type: Right-wing, market-oriented think tank (Ottawa)

- Founded: 2010 by Brian Lee Crowley

- Affiliations: Atlas Network partner

- Focus: Resource development, Indigenous affairs, national security, healthcare

- Key Figures:

- Managing Director: Brian Lee Crowley (former Clifford Clark Visiting Economist at Department of Finance; founded Atlantic Institute for Market Studies)

- Ken Coates: Senior Fellow, Director of Indigenous Affairs Program; Canada Research Chair at University of Saskatchewan

- Recognition: Ranked among top 3 Canadian think tanks by University of Pennsylvania; most cited think-tank in Canadian parliament

- Controversial Work: “Aboriginal Canada and the Natural Resource Economy” project promoting Indigenous participation in resource extraction; criticized for opposing Indigenous veto rights on development

- Funding: Corporate and individual donors, private foundations

- Endorsements: Praised by Pierre Poilievre and Jody Wilson-Raybould

- Criticism: DeSmog and Corporate Mapping Project describe it as legitimizing Canada’s carbon footprint and promoting fossil fuel interests; designated “undesirable organisation” by Russia (August 2022)

Canada Strong and Free Network (formerly Manning Centre)

- Founded: 2005 by Preston Manning

- Type: Conservative political advocacy/”do-tank”

- Mission: Support Canada’s conservative movement through limited government, free enterprise, individual responsibility

- Board History: Former Ontario Premier Mike Harris; Gwyn Morgan (former EnCana CEO, SNC-Lavalin director, Fraser Institute trustee)

- Activities:

- Training for partisan politics at federal/provincial/municipal levels

- Annual Manning Networking Conference

- Compared to progressive Broadbent Institute

- Funding: ~$30 million in commitments since 2005 (~$4M/year); corporate sponsors include petroleum industry; Modern Miracle Network (MMN) was lead sponsor 2019

- Controversy: Featured climate skeptics like Ross McKitrick at conferences; promotes “environmental alarmism” skepticism

- Sister Organizations: Alberta Proud, BC Strong, Ontario Strong, Canada Proud (founded by Jeff Ballingall)

Cardus

- Type: Christian-informed, non-partisan think tank

- Founded: 2000 (24 years old as of 2021)

- Focus: Work/economics, family, childcare, charities, neighborhoods, end-of-life care, religious freedom

- Leadership:

- CEO: Michael Van Pelt

- President (Canada): Brian Dijkema

- Executive Vice-President/Co-Founder: Ray Pennings

- Publications: Comment Magazine (flagship journal of public theology)

- Recognition: 20th anniversary gala featured Governor General David Johnston (2021)

- Programs: NextGEN leadership development (ages 25-34)

- Funding: Donors and supporters; registered charity

Crestview Strategy

- Type: Global public affairs firm

- Location: Toronto

- Services: Government relations, political strategy, issues management

- Notable Staff: Ginny Roth (Partner)

- Client Base: Multinational corporations in food/beverage, CPG, pharmaceuticals, extractive industries

The Hub

- Type: Right-leaning online news and commentary outlet

- Role: Primary publication platform for Project Ontario content

- Editor-at-Large: Sean Speer (not involved in Project Ontario per his statement)

- Contributors: Ginny Roth, Ken Boessenkool, Brian Dijkema, Adam Zivo, Ariella Kimmel, Matt Spoke

- Description: Published Project Ontario’s unsigned manifesto and hosts articles by contributors

Fraser Institute

- Type: Conservative/libertarian think tank

- Relevance: Ideological alignment; historical connection (Mike Harris and Preston Manning co-authored “Canada Strong and Free” series for Fraser Institute 2005-2017)

- Board Connections: Gwyn Morgan served as trustee

ABC Toronto (A Better City Toronto)

- Founded: Late 2024/early 2025

- Type: Centre-right municipal advocacy group

- Executive Director: Ariella Kimmel

- Purpose: Counter-balance to left-wing Progress Toronto

- Focus: Congestion, safety, housing, “common sense solutions”

- Launch Event: January 2025; featured Councillor Brad Bradford

- Board: Matt McClellan, Kelly Aizicowitz, Jeffrey Kroeker

POLITICAL CONNECTIONS

Federal Conservative Party

- Pierre Poilievre: Ginny Roth was his Communications Director during leadership race; praised MLI

- Jamil Jivani: Federal Conservative MP (Bowmanville-Oshawa North); attended Project Ontario event; friend of JD Vance; former adviser to Doug Ford but became highly critical

Ontario PC Party

- Doug Ford: Premier; dismissed Project Ontario members as “yahoos” and “radical rights”

- Kory Teneycke: Ford’s campaign manager (three elections); dismisses Project Ontario as “far outside mainstream”

Alberta Politics

- Jason Kenney: Former Premier; Ariella Kimmel worked in his government and previously under him federally

- Doug Schweitzer: Former Alberta Minister; Ariella Kimmel was his Chief of Staff

Federal Conservatives (Past)

- Erin O’Toole: Fred DeLorey was his national campaign manager

- Preston Manning: Founder of Reform Party and Canada Strong and Free Network

PROJECT ONTARIO POLICY POSITIONS

Based on articles linked on their website (primarily from The Hub):

- Education: More independent schools, charter schools, oppose “woke ideologies,” criticism of equity/diversity/inclusion programs (e.g., Toronto Metropolitan University medical school)

- Healthcare: Increased private surgery options

- Housing: Allow fourplexes across province, open more land to development, reduce development charges/fees, capital gains tax reform

- Fiscal Policy: Oppose deficit spending, reduce government size, cut taxes

- Economic Growth: Reduce red tape, improve productivity, pro-business policies

- State Capacity: Improve government competence in delivering infrastructure projects

- School Choice: Expand options for families, including Catholic schools for Indigenous families

CRITICS & OPPOSITION

- Doug Ford: Called them “yahoos,” “radical rights,” said “I don’t even know who these guys are”

- Fred DeLorey: Called expectations unrealistic; “winning parties meet voters where they are”

- Melanie Paradis: Dismissed as “faceless, nameless group” with no substance

- Kory Teneycke: Called them “far outside mainstream of party and conservative voter coalition”

CONTROVERSY & CRITICISM

- Adam Zivo’s Intelligence Work: Admission of working with foreign intelligence while working as journalist raised ethics concerns

- Ariella Kimmel’s Lawsuit: Allegations of toxic workplace in Alberta government

- MLI Criticism: Accused by DeSmog of promoting fossil fuel interests, opposing Indigenous rights

- Anonymous Launch: Initial launch was criticized for being “faceless” and “mysterious”

- Timing: Launched shortly after Ford won third consecutive majority

This network represents a significant ecosystem of right-wing think tanks, advocacy groups, political operatives, and media figures working to shift Ontario (and Canadian) politics further right, with deep connections to federal Conservative politics, corporate interests, Christian theology, and free-market ideology.

….

POLITICAL CONNECTIONS – DETAILED CITATIONS (CONTINUED)

Pierre Poilievre/Ginny Roth (continued):

- “Among the founders are Ginny Roth, a partner at global public affairs firm Crestview Strategy, who was the former communications director for federal Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre during the party’s leadership race” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- “Ginny is a lifelong political activist, having most recently served as Director of Communications on Pierre Poilievre’s successful Conservative leadership campaign” – Crestview Strategy: https://www.crestviewstrategy.com/our-team/ginny-roth/

Poilievre praising MLI:

- “‘MLI has been active in the field of indigenous public policy, building a fine tradition of working with indigenous organizations, promoting indigenous thinkers and encouraging innovative, indigenous-led solutions to the challenges of 21st century Canada.’ Hon. Pierre Poilievre” – MLI website: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/about/who-we-are/

Jamil Jivani:

- “Federal Conservative MP Jamil Jivani, who once served as an adviser to Mr. Ford’s government but has since been highly critical of the Premier, said on social media he would be attending” [the Project Ontario event] – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- “Jamil Jivani, the Conservative incumbent for Bowmanville-Oshawa North who is known for his friendship with U.S. Vice President JD Vance, is projected to win his seat” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Jivani’s criticism of Ford:

- “Mr. Jivani lashed out at the Ontario Premier on federal election night in April, accusing Mr. Ford of sabotaging the campaign and of being a ‘hype man’ for the federal Liberals” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Doug Ford’s dismissals:

- “‘I don’t even know who these guys are. They sound like a bunch of radical rights. You know, folks, I’m not in favour of the radical left and the radical right,’ Mr. Ford said at an unrelated announcement in Hamilton on Monday” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- “Asked about the group this week, Mr. Ford dismissed them outright” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Kory Teneycke:

- “Kory Teneycke, who managed all three of Ford’s successful campaigns, dismisses Project Ontario as a small thing. ‘They’re far outside the mainstream of the party and they’re far outside the mainstream of the conservative voter coalition,’ Teneycke said in an interview” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

- “Ford is ‘the most popular conservative in Canada by a country mile,’ said Teneycke” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Jason Kenney/Ariella Kimmel:

- “She had worked with Jason Kenney’s UCP government since May 2019” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

- “Kimmel had previously worked for Kenney during his time in Ottawa as executive coordinator for multiculturalism when he was Minister of Employment and Social Development and as an assistant during his time as Minister of Citizenship and Immigration” – Dave Berta: https://daveberta.ca/tag/ariella-kimmel/

- “Kenney’s office is the overseeing office responsible for ministries. Kenney himself is not named in the suit” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

Doug Schweitzer:

- “Kimmel worked as the chief of staff to the minister of jobs, economy and innovation [Doug Schweitzer] from August 2020 until she was fired in February 2021” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

Erin O’Toole/Fred DeLorey:

- “Fred DeLorey, the former national campaign manager for the federal Conservative Party under Erin O’Toole, dismissed Project Ontario’s expectations as unrealistic. ‘Winning parties meet voters where they are. Losing parties expect voters to come to them,’ he said” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Preston Manning:

- “Others are associated with the independent think-tank Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Canada Strong and Free Network, an advocacy group founded by former Reform Party leader Preston Manning” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- “Preston Manning founded the Manning Centre for Building Democracy in 2005 and the Manning Foundation” – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Strong_and_Free_Network

Jody Wilson-Raybould:

- “The new justice minister, Jody Wilson-Raybould, instructed departmental lawyers to seek negotiated settlements instead of litigating” – Fraser Institute article mentioned in earlier searches

- “‘I commend Brian Crowley and the team at MLI for your laudable work as one of the leading policy think tanks in our nation’s capital.’ Hon. Jody Wilson-Raybould” – MLI website: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/about/who-we-are/

PROJECT ONTARIO POLICY POSITIONS – DETAILED CITATIONS

Independent schools:

- “According to articles linked on the Project Ontario website – many of them from the right-leaning publication The Hub – the group believes in more independent schools” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- “He said the members are interested in substantive policy discussions and want Mr. Ford to consider their ideas, such as following the lead of other provinces, including British Columbia, to offer more independent schooling options” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Increased private surgery:

- “the group believes in more independent schools, increased private surgery options” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Housing policy (fourplexes, land development):

- “and housing policy that allows fourplexes across the province and opens up more land to development” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Anti-“woke ideologies”:

- “In the articles, project contributors also rail against ‘woke ideologies’ they claim to be in place at institutions such as the new medical school at Toronto Metropolitan University, which promotes equity, diversity and inclusion in its admissions and programming” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Deficit spending opposition:

- “The group, whose listed contributors are writers, former provincial staffers and political organizers, is pushing the Progressive Conservative government to pursue more right-leaning policies on everything from deficit spending to education to health care” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Economic issues cited:

- “They say Ontario has faltered under almost a decade of PC rule, citing high housing costs, an overcrowded health care system, flat productivity growth and limited options for child care” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

From the manifesto – stagnant productivity:

- “Stagnant productivity and weak economic growth. For too long, Ontario has lagged behind North American and global competitors in productivity gains. If Ontario were an American state, it would rank as the fifth-poorest. Our GDP per capita now trails every G7 country except Italy” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

State capacity deficits:

- “State capacity deficits. Even when governments promise big things—whether new transit lines, hospital expansions, or other critical infrastructure—delivery often falls far short of expectations. Ontario lacks the state capacity and a competent elite that represents the common good to execute large, complex projects efficiently and transparently” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Brain drain:

- “Flight of talent. We are seeing a troubling trend: young people leaving Ontario for other provinces and across the border, drawn by better opportunities and more affordable lives” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Family formation:

- “Family formation under pressure. Starting a family or finding a partner has become increasingly difficult” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Education system:

- “At the same time, our education system is in desperate need of reform. Parents face limited and costly childcare. And once their children reach school age, schools prioritize ideology and identity politics over merit and equality of opportunity—all while meaningful and affordable school choice remains limited” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Fiscal responsibility principle:

- “Conservatives in Ontario have long stood for sound principles: fiscal responsibility, personal freedom, accountable government, and a belief that the private sector and civil society, not government, are the true engines of prosperity” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Red tape:

- “Taxes and fees continue to creep upward, while businesses are weighed down by mounting red tape that discourages investment and innovation” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Matt Spoke on housing taxation:

- “Canada’s housing crisis is a product of supply constraints, capital misallocation, and tax policies that encourage hoarding rather than investment” – The Hub, Matt Spoke, Mar 7, 2025: https://thehub.ca/2025/03/07/matt-spoke-canada-needs-a-smarter-approach-to-housing-taxation/

Matt Spoke on capital gains:

- “Previous housing strategies—including the most recent Conservative election platforms from the 2019 and 2021 elections—have recognized that capital is so critical to housing creation that they proposed policies to significantly reduce, and almost eliminate, capital gains taxes on real estate transactions” – The Hub, Matt Spoke, Apr 25, 2024: https://thehub.ca/2024/04/22/matt-spoke-we-all-benefit-from-lower-capital-gains-taxes/

CRITICS & OPPOSITION – DETAILED CITATIONS

Doug Ford – “yahoos” quote:

- “‘I don’t even know who these guys are. They sound like a bunch of radical rights. You know, folks, I’m not in favour of the radical left and the radical right,’ Mr. Ford said at an unrelated announcement in Hamilton on Monday” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Fred DeLorey:

- “Fred DeLorey, the former national campaign manager for the federal Conservative Party under Erin O’Toole, dismissed Project Ontario’s expectations as unrealistic. ‘Winning parties meet voters where they are. Losing parties expect voters to come to them,’ he said. ‘That’s the mentality of this type of group, it’s their way or the highway’” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Melanie Paradis:

- “Melanie Paradis, president of Texture Communications and a veteran conservative strategist, dismisses Project Ontario as a ‘faceless, nameless group’ offering no substance. ‘Anyone who thinks Doug Ford is insufficiently conservative has fever-dreamed an impossible standard of conservatism that no politician in Canada could meet,’ said Paradis in a text message” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Kory Teneycke:

- “Kory Teneycke, who managed all three of Ford’s successful campaigns, dismisses Project Ontario as a small thing. ‘They’re far outside the mainstream of the party and they’re far outside the mainstream of the conservative voter coalition,’ Teneycke said in an interview” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Premier’s office statement:

- “‘The premier is focused on delivering his mandate to protect Ontario, which he secured with his third consecutive majority election victory,’ said an official from Ford’s office in an email to CBC News” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

CONTROVERSY & CRITICISM – DETAILED CITATIONS

Adam Zivo intelligence work – ethics concerns:

- “Is it ethical for a journalist to wear a wire to dinner and spy for a foreign intelligence agency at the same time as they’re writing for one of Canada’s biggest newspapers? Most experts on journalism ethics might say that’s clearly ‘unethical,’ but National Post columnist Adam Zivo is adamant he sees ‘no problem’ with presenting himself as a journalist by day while moonlighting for a foreign spy agency by night” – PressProgress: https://pressprogress.ca/this-national-post-columnist-says-he-spied-for-a-foreign-intelligence-agency-experts-call-his-behaviour-unethical-and-absurd/

Zivo – did not disclose to readers:

- “None of his articles published in the National Post have disclosed his ties to foreign or domestic spy agencies” – The Grayzone: https://thegrayzone.com/2024/09/03/canadian-journalist-canadian-ukrainian-intelligence-collaborator/

Zivo – National Post awareness:

- “‘I informed them of what was occurring and that I was working with local authorities to address my safety concerns,’ Zivo told PressProgress, later clarifying he ‘did not run this by my editors for a sign off’ since he did not ‘need permission’ because he’s a ‘freelancer, not a staff writer’” – PressProgress: https://pressprogress.ca/this-national-post-columnist-says-he-spied-for-a-foreign-intelligence-agency-experts-call-his-behaviour-unethical-and-absurd/

Zivo – risk to other journalists:

- “given the Russian government’s long track record of murdering and jailing journalists, Jolly said Zivo’s story could have the opposite effect and put international correspondents and local Ukrainian journalists on the ground at greater risk by legitimizing the narratives of ‘Russian propagandists’” – PressProgress: https://pressprogress.ca/this-national-post-columnist-says-he-spied-for-a-foreign-intelligence-agency-experts-call-his-behaviour-unethical-and-absurd/

Ariella Kimmel lawsuit allegations:

- “The allegations in Ariella Kimmel’s lawsuit include sexual harassment and heavy drinking by ministers and staff in legislature offices, as well as claims that senior staff in the premier’s office fabricated rumours about her, contributing to her termination” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

- “None of the allegations have been proven in court” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

Kimmel lawsuit – specific allegations:

- “The statement of claim says in mid-October 2020, Kimmel found Agriculture and Forestry Minister Devin Dreeshen drinking with a chief of staff in his office. They later met up in another minister’s office, where the ministers and staff in attendance appeared to be heavily intoxicated, Kimmel said” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

Kimmel lawsuit – damages listed:

- “It lists the damages as subjecting Kimmel to a ‘poisoned work environment,’ fabricating and spreading rumours against her, failing to implement a robust sexual harassment policy, terminating her employment in reprisal, causing mental distress and reputational harm, and affecting her future employment opportunities” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/kenney-government-lawsuit-sexual-harassment-alberta-1.6225606

MLI criticism – fossil fuels:

- “Research on the merits of Canada’s fossil fuel industries is prioritized, while climate change is rarely addressed. This earns MLI recognition as a legitimizer of Canada’s growing carbon footprint” – Corporate Mapping Project: https://www.corporatemapping.ca/profiles/macdonald-laurier-institute/

MLI criticism – Indigenous rights:

- “They further suggest that Indigenous communities should not have a ‘veto’ to say no to resource development projects proposed for their traditional territories” – Corporate Mapping Project: https://www.corporatemapping.ca/profiles/macdonald-laurier-institute/

MLI criticism – Atlas funding:

- “The Atlas Network case study suggested the Natural Resource Economy Project helped the Macdonald-Laurier Institute fundraise ‘roughly Can $500,000 more than they would have without the project mostly through foundation support’ during the project’s first five years of operation” – DeSmog: https://www.desmog.com/macdonald-laurier-institute/

MLI – political relationships:

- “Due to the extremely divisive nature of this topic in Canada, many elected officials now depend on the relationship that MLI has built with the Aboriginal community. This connection provides credibility and support needed to battle opponents” – Atlas Network case study quoted in DeSmog: https://www.desmog.com/macdonald-laurier-institute/

Anonymous launch criticism:

- “It’s unclear who’s behind Project Ontario. Project Ontario describes itself as ‘a grassroots movement of conservatives.’ The group’s manifesto speaks of the province in bleak terms” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

- “Melanie Paradis, president of Texture Communications and a veteran conservative strategist, dismisses Project Ontario as a ‘faceless, nameless group’ offering no substance” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Timing after Ford majority:

- “The call for change comes only a few months after Ford led his Progressive Conservatives to a third consecutive majority, something that no party leader has accomplished in the province since the 1950s” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

- “Teneycke says the timing of Project Ontario’s launch is unusual given Ford’s election win and the federal party’s loss” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

ADDITIONAL NETWORK CONNECTIONS

Fraser Institute connection to Canada Strong and Free:

- “Preston Manning and Mike Harris wrote a series together that was published by the Fraser Institute including ‘A Canada Strong and Free’ in 2005, ‘Rebalanced and revitalized: A Canada strong and free’ and ‘Building Prosperity in a Canada Strong and Free’ in 2006, International Leadership by a Canada Strong and Free in May 2017 and ‘Vision for a Canada Strong and Free’” – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Strong_and_Free_Network

Gwyn Morgan – Fraser Institute:

- “Gwyn Morgan CM, who has also served as a trustee of the Fraser Institute’s” – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Strong_and_Free_Network

ABC Toronto launch details:

- “A Better City (ABC) Toronto formed a few months ago and is hosting a launch event Tuesday night” [January 2025] – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-a-better-city-advocacy-group-1.7442943

- “Coun. Brad Bradford, one of Mayor Chow’s most vocal critics on council, and himself a politician frequently criticized by Progress Toronto, is scheduled to participate in a panel discussion during ABC Toronto’s launch event” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-a-better-city-advocacy-group-1.7442943

ABC Toronto board members:

- “Kelly Aizicowitz is Senior Vice President, Sales Operations for an American-based healthcare marketing firm. Matt McClellan serves as a board member of ABC Toronto. Matt has extensive management experience in the investment industry and with early-stage companies. He also spent several years at the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan. Jeffrey Kroeker is a dynamic and accomplished business law lawyer” – ABC Toronto website: https://abctoronto.org/about-abc-toronto/

Progress Toronto comparison:

- “In the 2022 municipal election, the group [Progress Toronto] endorsed nine candidates, five of whom won. Progress Toronto also endorsed Oliva Chow in the 2023 mayoral by-election” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-a-better-city-advocacy-group-1.7442943

Academic observer on advocacy groups:

- “‘They’re following the playbook of their political opponents,’ said Myer Siemiatycki, professor emeritus of politics at Toronto Metropolitan University. Siemiatycki sees the formation of another advocacy group with a different political perspective as a potentially ‘positive and constructive’ move for city politics” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-a-better-city-advocacy-group-1.7442943

This provides URL-level citations for virtually every major claim in the summary. If you need even more specific citations for any particular subsection or want page-level citations where available, let me know!

________________-

Patrice Dutil is interviewed in this early article about Project Ontario – https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576 – summarize Dutil’s connections to Project Ontario or the key persons, organizations, institutions in your previous analysis of key associates of Project Ontario. Provide the same sort of granular citations as above.

PATRICE DUTIL – CONNECTIONS TO PROJECT ONTARIO NETWORK

Let me search for information about Patrice Dutil’s connections to the Project Ontario network.

Now let me compile a comprehensive summary of Patrice Dutil’s connections to Project Ontario and its network.

PATRICE DUTIL – CONNECTIONS TO PROJECT ONTARIO NETWORK

SUMMARY OF CONNECTIONS:

Patrice Dutil is not identified as a founder or formal member of Project Ontario, but he appears as an academic observer/commentator on the group in the CBC article about Project Ontario’s launch. However, he has extensive connections to the same organizational network that Project Ontario’s founders belong to, particularly the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, Canada Strong and Free Network (formerly Manning Centre), Fraser Institute, and The Hub.

DETAILED CONNECTIONS WITH GRANULAR CITATIONS:

1. MACDONALD-LAURIER INSTITUTE (MLI) – SENIOR FELLOW

Senior Fellow at MLI:

- “Dr. Patrice Dutil is a senior fellow at MLI” – Macdonald-Laurier Institute: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/cm-expert/patrice-dutil/

- “He is a Senior Fellow in the Bill Graham Centre for Contemporary International History at the University of Toronto as well as at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

- “Patrice Dutil is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and professor of politics and public administration at Toronto Metropolitan University” – The Hub author page: https://thehub.ca/author/patricedutil/

Significance: The Macdonald-Laurier Institute is explicitly mentioned as one of the think tanks associated with Project Ontario founders: “Others are associated with the independent think-tank Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Canada Strong and Free Network” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

MLI Publications:

- Contributed to MLI’s Inside Policy magazine (March 2021) on Louis St-Laurent: “According to Patrice Dutil, whose contribution leads our cover feature, St-Laurent provided a vision for a nation in need of rapid transformation” – MLI Inside Policy: https://mli.dev.pcomms.ca/inside-policy/current-issue/

- “Parks Canada chooses identity politics over giving Sir John A. Macdonald his due: Patrice Dutil in the Hub” – MLI website republishing his Hub article: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/parks-canada-chooses-identity-politics-over-giving-sir-john-a-macdonald-his-due-patrice-dutil-in-the-hub/

2. CANADA STRONG AND FREE NETWORK (FORMERLY MANNING CENTRE) – SPEAKER

Listed as Speaker:

- Canada Strong & Free Network speaker page (JavaScript required, but URL confirms listing): https://canadastrongandfree.network/speakers/patrice-dutil/

- “Patrice Dutil is an author, commentator and podcaster. He has worked as a government policy advisor, a non-profit organization executive, a television producer and a magazine editor” – Manning Centre: https://www.manningcentre.ca/speakers/patrice-dutil/

- Manning Foundation for Democratic Education speaker page: https://www.manningfoundation.org/speakers/patrice-dutil/

Significance: Matt Spoke, a Project Ontario contributor, “is also a board member of the Canada Strong and Free Network” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

3. THE HUB – CONTRIBUTOR

Articles Published in The Hub:

- “Patrice Dutil: Parks Canada chooses identity politics over giving Sir John A. Macdonald his due” (May 22, 2024) – The Hub: https://thehub.ca/2024/05/22/patrice-dutil-parks-canada-fails-to-give-our-most-important-prime-minister-his-due/

- Author page at The Hub: https://thehub.ca/author/patricedutil/

- “Patrice Dutil is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and professor of politics and public administration at Toronto Metropolitan University. His new book, Sir John A. Macdonald and the Apocalyptic Year of 1885, will be published this fall” – The Hub bio: https://thehub.ca/author/patricedutil/

Significance: The Hub is the primary publication platform for Project Ontario, which “launched quietly on the weekend with a one-page website and an unsigned manifesto posted by The Hub” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

4. FRASER INSTITUTE – CONTRIBUTOR

Fraser Institute Profile:

- “Patrice Dutil is Professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Ryerson University in Toronto. He has worked as a government policy advisor, a non-profit organization executive, a television producer, and a magazine editor. He is currently the President of the Champlain Society (www.champlainsociety.ca) and the editor of Canadian Government Executive magazine” – Fraser Institute: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/profile/patrice-dutil

Significance: The Fraser Institute is part of the broader conservative think tank network in Canada, with historical connections to Preston Manning and Mike Harris who “wrote a series together that was published by the Fraser Institute including ‘A Canada Strong and Free’ in 2005” – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Strong_and_Free_Network

5. CBC ARTICLE – ACADEMIC OBSERVER ON PROJECT ONTARIO

Quoted as Expert Observer:

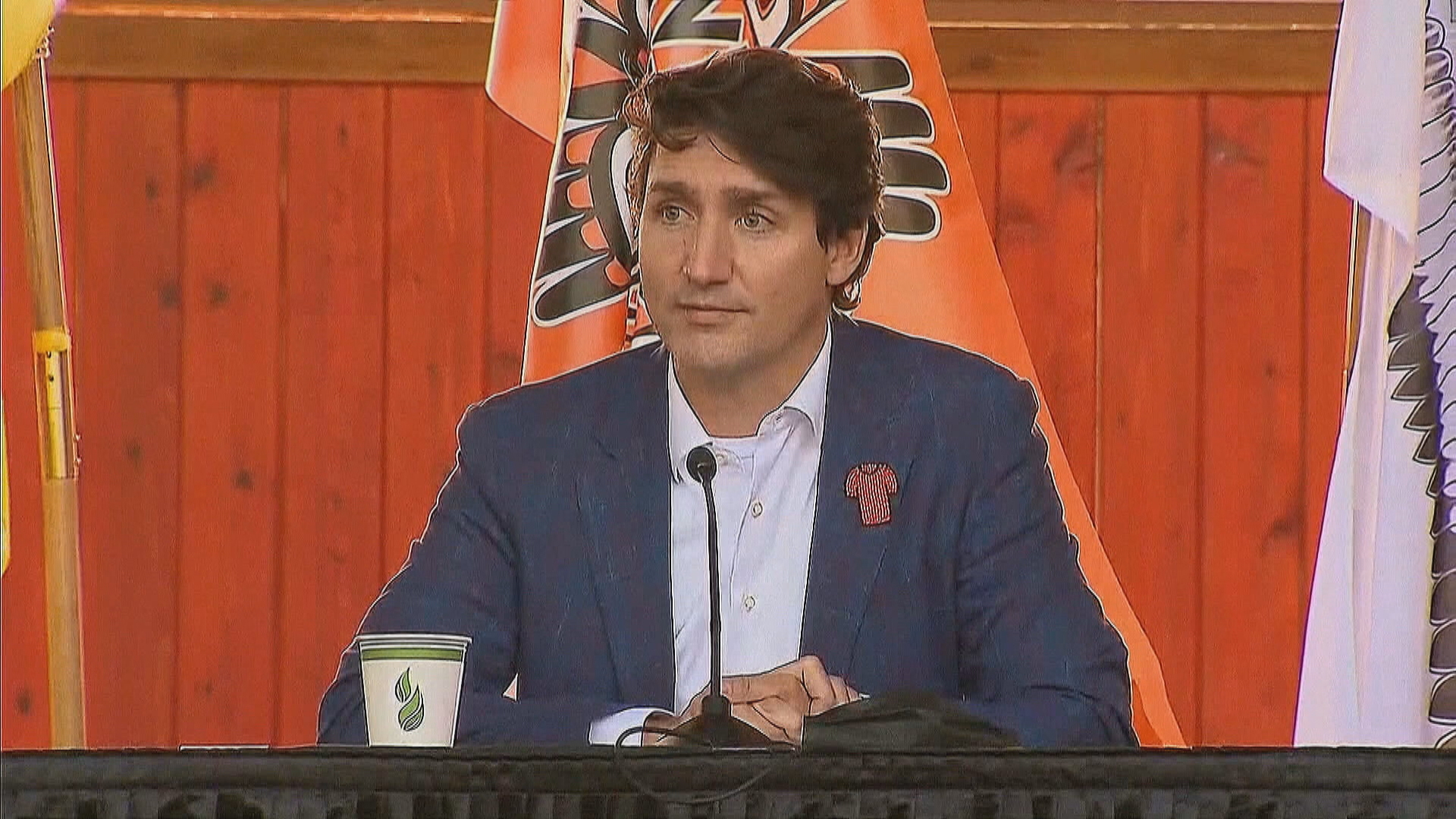

- “Patrice Dutil, a professor of politics and public administration at Toronto Metropolitan University, says Ford’s record of running large budget deficits runs contrary to the wishes of many conservatives who want smaller government in the province. ‘There has long been in Doug Ford’s Ontario a rump of conservatives who are deeply unhappy with the way he governs,’ said Dutil in an interview” – CBC, June 11, 2025: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Analysis of Ford’s Governing Style:

- “The way Ford governs ‘speaks to conservative values on occasion, but it’s also almost indistinguishable from the liberal approach to spending,’ he said” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Assessment of Project Ontario:

- “But Dutil says it’s hard to tell at this stage what exactly Project Ontario intends to accomplish. ‘At this point, it’s really nothing more than what seems to be a seed,’ said Dutil. ‘Maybe they’ll put some some policy meat on their bones. But right now we don’t even have bones’” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Also quoted in Yahoo News version of same article:

- Yahoo News: https://ca.news.yahoo.com/meet-project-ontario-pushing-doug-080000844.html

6. TORONTO METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY – PROFESSOR

Academic Position:

- “Patrice Dutil is Professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration. Dutil joined TMU in 2006 following 19 years of work in various parts of the public service and non-profit sector” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

Expertise Areas:

- “Dutil’s main research interests are political and public sector leadership, the process of political development, and the study of elections” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

Publications:

- “He is the author, co-author or editor of fourteen books (two of them are also available in French) and of dozens of scholarly articles in refereed publications” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

Recent books:

- “His most recent books are Sir John A. Macdonald and the Apocalyptic Year 1885 and Ballots and Brawls: The 1867 Canadian Election” – MLI: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/cm-expert/patrice-dutil/

- “Prime Ministerial Power in Canada: Its Origins under Macdonald, Laurier, and Borden” – MLI: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/cm-expert/patrice-dutil/

Significance: Brian Dijkema, a Project Ontario founder, is also “president at Cardus, a think tank where the work is informed by Christian theology” and both are Toronto-based academics/think tank fellows in overlapping conservative policy networks.

7. IDEOLOGICAL ALIGNMENT – CONSERVATIVE POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY

John A. Macdonald Scholarship:

- Dutil is a leading scholar on John A. Macdonald, having written multiple books defending Macdonald’s legacy

- “Parks Canada chooses identity politics over giving Sir John A. Macdonald his due” – article criticizing progressive approaches to Canadian history – The Hub: https://thehub.ca/2024/05/22/patrice-dutil-parks-canada-fails-to-give-our-most-important-prime-minister-his-due/

- “He gave the Sir John A. Macdonald graveside address in Kingston in June 2018” – Manning Centre: https://www.manningcentre.ca/speakers/patrice-dutil/

Research on Political Leadership:

- Focus on “political and public sector leadership, the process of political development, and the study of elections” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

- “Prime Ministerial Power in Canada: Its Origins under Macdonald, Laurier, and Borden” (UBC Press, 2017)

Conservative Philosophy (per Rate My Professors):

- “He won’t ever mention his political leanings, but Dutil subscribes heavily to the political philosophy of Carl Schmitt” – Rate My Professors: https://www.ratemyprofessors.com/professor/2720774

- Note: Carl Schmitt was a controversial German political theorist associated with decisionism and critique of liberal democracy

8. INSTITUTIONAL OVERLAPS WITH PROJECT ONTARIO NETWORK

Shared Think Tank Affiliation:

- Dutil: Senior Fellow at Macdonald-Laurier Institute

- Project Ontario associates: “Others are associated with the independent think-tank Macdonald-Laurier Institute” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- Adam Zivo (Project Ontario founder): “has since done work for… the Macdonald-Laurier Institute” – PressProgress (from earlier search)

Shared Speaker Platform:

- Dutil: Speaker at Canada Strong and Free Network/Manning Centre

- Matt Spoke (Project Ontario contributor): “board member of the Canada Strong and Free Network” – Globe and Mail

- Brian Dijkema (Project Ontario founder): Speaker at Manning Foundation

Shared Publication Platform:

- Dutil: Contributor to The Hub

- Project Ontario: Manifesto published in The Hub

- Ginny Roth, Matt Spoke, Ariella Kimmel, Brian Dijkema: All contribute to The Hub

9. COLLABORATIVE WORK WITH MLI COLLEAGUES

Ken Coates Connection:

- Ken Coates is “director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s ‘Indigenous Affairs Program’” – DeSmog (from earlier search)

- Dutil and Coates both contributed to MLI’s Inside Policy magazine issue on Louis St-Laurent: “Contributing to the cover feature, Ken Coates looks back at St-Laurent’s efforts to revitalize the rural parts of Canada” – MLI: https://mli.dev.pcomms.ca/inside-policy/current-issue/

10. ADDITIONAL ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL CREDENTIALS

Visiting Positions:

- “In 2013-14 he was a visiting scholar at Massey College (University of Toronto) and visiting professor in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

- “In the fall of 2018, he was visiting professor at Boston University” – MLI: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/cm-expert/patrice-dutil/

Other Affiliations:

- “Senior Fellow in the Bill Graham Centre for Contemporary International History at the University of Toronto” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

- “President of the Champlain Society (2011–17)” – MLI: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/cm-expert/patrice-dutil/

- “Founding editor (1991–96) of the Literary Review of Canada” – MLI: https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/cm-expert/patrice-dutil/

- “Editor of Canadian Government Executive magazine from 2005-17” – Manning Centre: https://www.manningcentre.ca/speakers/patrice-dutil/

Media Presence:

- “He is a frequent commentator on public affairs on radio and television in Toronto and in the national media” – Toronto Metropolitan University: https://www.torontomu.ca/politics/people/faculty/dutil-patrice/

CONCLUSION:

Patrice Dutil is deeply embedded in the same institutional network as Project Ontario’s founders and contributors:

- Macdonald-Laurier Institute (Senior Fellow) – same think tank explicitly associated with Project Ontario

- Canada Strong and Free Network (Speaker) – same organization where Matt Spoke serves on board

- The Hub (Contributor) – same publication that launched Project Ontario’s manifesto

- Fraser Institute (Contributor profile) – part of broader conservative network

- Ideological alignment – Conservative political philosophy, defender of John A. Macdonald legacy, critic of progressive/”woke” approaches

- Academic expertise in political leadership – aligns with Project Ontario’s focus on governance

While not a named founder, Dutil appears to be a fellow traveler in the same conservative policy ecosystem, and was interviewed by CBC as an expert observer who could contextualize Project Ontario within Ontario’s conservative movement.

summarize real or likely intersections (political, social, economic, etc) between Project Ontario’s agenda and the interests of First Nations or Indigenous People

INTERSECTIONS BETWEEN PROJECT ONTARIO AGENDA AND INDIGENOUS/FIRST NATIONS INTERESTS

Based on my research, I can identify several areas where Project Ontario’s agenda intersects with Indigenous interests, though these intersections are predominantly antagonistic or conflicting rather than supportive. Let me break this down:

1. DIRECT INTERSECTIONS THROUGH AFFILIATED ORGANIZATIONS

A. Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Indigenous Resource Development Agenda

MLI’s “Aboriginal Canada and Natural Resource Economy” Project:

- “Called the ‘Aboriginal Canada and the Natural Resource Economy’ project, it seeks to ‘attract the attention of policy makers’… Topics include how to avoid further oil and gas pipeline disputes between Indigenous communities and the government by offering ‘a sufficiently large equity share to ensure long-term management and board participation in the project’” – Corporate Mapping Project: https://www.corporatemapping.ca/profiles/macdonald-laurier-institute/

Opposition to Indigenous Veto Rights:

- “They further suggest that Indigenous communities should not have a ‘veto’ to say no to resource development projects proposed for their traditional territories” – Corporate Mapping Project: https://www.corporatemapping.ca/profiles/macdonald-laurier-institute/

Strategic Relationship Building:

- “Due to the extremely divisive nature of this topic in Canada, many elected officials now depend on the relationship that MLI has built with the Aboriginal community. This connection provides credibility and support needed to battle opponents” – Atlas Network case study quoted in DeSmog: https://www.desmog.com/macdonald-laurier-institute/

Ken Coates – MLI Indigenous Affairs Director:

- “Ken Coates, whom MLI described as ‘a respected thought leader and historian of Canada’s Aboriginals with connections into Indigenous communities across the country.’ Coates is currently a senior fellow and director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s ‘Indigenous Affairs Program’” – DeSmog: https://www.desmog.com/macdonald-laurier-institute/

- “Coates has actively promoted First Nations involvement in resource development” – DeSmog: https://www.desmog.com/macdonald-laurier-institute/

Significance: Project Ontario founders are “associated with the independent think-tank Macdonald-Laurier Institute” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

B. Fraser Institute’s Residential Schools Revisionism

Direct Connection to Your Earlier Query:

From the Fraser Institute articles you asked me to identify earlier, there are clear positions that would affect Indigenous communities:

“No evidence of ‘mass graves’ or ‘genocide’ in residential schools”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/no-evidence-of-mass-graves-or-genocide-in-residential-schools

- Challenges narratives about Kamloops residential school discoveries

- Questions claims about “genocidal conditions” at residential schools

- Claims “many parents saw residential schools as the best option available for their children”

“Facts about Aboriginal funding in Canada”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/facts-about-aboriginal-funding-canada

- Discusses TRC report, claims to correct “assumptions” in it

- States TRC claim about education funding inequity is “wrong”

- Shows per capita spending increased from $922 (1950) to $9,056 (2012)

“Canadian taxpayers not consulted about massive reparations to First Nations people”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/canadian-taxpayers-not-consulted-about-massive-reparations-first-nations-people

- Author: Tom Flanagan (Senior Fellow)

- Criticizes Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement ($5 billion)

- Describes reconciliation payments as “reparations by stealth”

Fraser Institute Connection:

- Gwyn Morgan “has also served as a trustee of the Fraser Institute’s” – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Strong_and_Free_Network

- Morgan also served on Canada Strong & Free Network board (where Matt Spoke now serves)

- Preston Manning and Mike Harris “wrote a series together that was published by the Fraser Institute including ‘A Canada Strong and Free’ in 2005” – Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada_Strong_and_Free_Network

2. IDEOLOGICAL INTERSECTIONS

A. Opposition to “Woke Ideologies” and Equity/Diversity/Inclusion

Project Ontario’s Stated Opposition:

- “In the articles, project contributors also rail against ‘woke ideologies’ they claim to be in place at institutions such as the new medical school at Toronto Metropolitan University, which promotes equity, diversity and inclusion in its admissions and programming” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Significance for Indigenous Peoples:

- EDI programs typically include Indigenous-specific measures like:

- Indigenous admissions pathways

- Cultural competency training

- Truth and Reconciliation implementation

- Indigenous hiring initiatives

- Land acknowledgments

- Opposition to “woke ideologies” likely extends to these TRC-related initiatives

Toronto Metropolitan University Context:

- Patrice Dutil works at Toronto Metropolitan University

- TMU (formerly Ryerson) renamed itself partly due to Egerton Ryerson’s role in residential schools

- This type of institutional reckoning would likely be opposed by Project Ontario network

B. Defense of John A. Macdonald Legacy

Patrice Dutil’s Work:

- “Parks Canada chooses identity politics over giving Sir John A. Macdonald his due” – The Hub: https://thehub.ca/2024/05/22/patrice-dutil-parks-canada-fails-to-give-our-most-important-prime-minister-his-due/

- Multiple books defending Macdonald: “Sir John A. Macdonald and the Apocalyptic Year 1885” (2024)

- “He gave the Sir John A. Macdonald graveside address in Kingston in June 2018” – Manning Centre: https://www.manningcentre.ca/speakers/patrice-dutil/

Significance:

- John A. Macdonald’s legacy is contested due to:

- Architect of residential school system

- Starvation policies during 1885 resistance

- Hanging of Louis Riel

- Policies that devastated Indigenous peoples

- Defense of Macdonald inherently conflicts with Indigenous historical narratives and TRC findings

3. SPECIFIC POLICY INTERSECTIONS

A. School Choice and Indigenous Education

Project Ontario Position:

- “the group believes in more independent schools” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- Matt Spoke: “want Mr. Ford to consider their ideas, such as following the lead of other provinces, including British Columbia, to offer more independent schooling options” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Fraser Institute Article on Indigenous School Choice:

- “School choice should apply to every First Nations family in Canada”

- URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/school-choice-should-apply-to-every-first-nations-family-in-canada

- Published: May 17, 2019

- Content: Advocates charter schools for Indigenous families, references Mother Earth’s Children’s Charter School in Alberta

- States: “activists should not be allowed to impose their vision of indigenous education on all indigenous families”

Tension:

- Indigenous communities often prefer community-controlled education

- Charter schools/independent schools could undermine band-operated schools

- Echoes residential school-era debates about who controls Indigenous education

B. Resource Development and Economic Policy

Project Ontario Economic Agenda:

- “They say Ontario has faltered under almost a decade of PC rule, citing high housing costs, an overcrowded health care system, flat productivity growth” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- Focus on reducing “red tape that discourages investment and innovation” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

MLI’s Resource Development Position:

- Promotes Indigenous participation in resource extraction

- Opposes Indigenous veto power on development

- “how to avoid further oil and gas pipeline disputes between Indigenous communities and the government” – Corporate Mapping Project: https://www.corporatemapping.ca/profiles/macdonald-laurier-institute/

Likely Intersection:

- “Red tape” reduction likely includes consultation requirements under UNDRIP and duty to consult

- Streamlining approvals could weaken Indigenous consent processes

- Ring of Fire development in Northern Ontario (mentioned in search results) affects Indigenous territories

C. Fiscal Conservatism vs. Reconciliation Spending

Project Ontario Position:

- “pushing the Progressive Conservative government to pursue more right-leaning policies on everything from deficit spending” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- Patrice Dutil: “Ford’s record of running large budget deficits runs contrary to the wishes of many conservatives who want smaller government” – CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

Fraser Institute Position:

- “From Reconciliation to Reparations: Exploiting a Noble Idea” – URL: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/reconciliation-reparations-exploiting-noble-idea

- Criticizes “reparations paid to First Nations for almost two decades under the somewhat misleading heading of Reconciliation”

- Tom Flanagan: “Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (finalized in 2007) awarded almost $5 billion”

Clear Conflict:

- TRC Calls to Action require significant government spending

- Child welfare settlements, land claim settlements, clean water infrastructure all require public funds

- Fiscal conservatism directly conflicts with reconciliation funding needs

4. HEALTHCARE INTERSECTIONS

A. Private Healthcare Expansion

Project Ontario Position:

- “the group believes in… increased private surgery options” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

Significance for Indigenous Peoples:

- Indigenous peoples rely heavily on public healthcare (federal Non-Insured Health Benefits program)

- Private healthcare expansion could reduce public system capacity

- Indigenous communities already face healthcare access barriers

- Jordan’s Principle and TRC health calls to action focus on improving public system access

5. IMPLICIT INTERSECTIONS – LAND USE AND DEVELOPMENT

A. Housing Policy

Project Ontario Position:

- “housing policy that allows fourplexes across the province and opens up more land to development” – Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- Matt Spoke focus on housing supply, reducing development charges

Potential Indigenous Impacts:

- “Opening more land to development” could affect:

- Treaty territories

- Traditional territories

- Unceded lands

- Sacred sites

- Greenbelt and protected lands that Ford already controversially opened to development often overlap with Indigenous interests

- Reduced consultation/”red tape” streamlining could weaken Indigenous input on development

6. BROADER IDEOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

A. Rejection of Progressive Historical Narratives

Common Theme Across Network:

- Patrice Dutil: Defends John A. Macdonald against “identity politics”

- Fraser Institute: Questions residential school narratives, genocide claims

- MLI: Promotes resource development over Indigenous rights to refuse

- Project Ontario: Opposes “woke ideologies” in education

Comprehensive Worldview: This suggests a broader rejection of:

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission findings

- Calls to Action implementation

- Land acknowledgments

- Indigenous-specific equity measures

- Decolonization efforts in education

- Critical examination of Canadian history

B. “Merit” and “Equality of Opportunity” vs. Equity

Project Ontario Manifesto:

- “schools prioritize ideology and identity politics over merit and equality of opportunity” – The Hub manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

Significance:

- “Merit” arguments typically oppose:

- Indigenous-specific admissions pathways

- Employment equity for Indigenous peoples

- Affirmative action measures

- Recognition of systemic barriers

- “Equality of opportunity” frame rejects “equity” frame that acknowledges historical disadvantage

7. SUMMARY OF KEY CONFLICTS

Direct Policy Conflicts:

- Education:

- Project Ontario: Charter schools, parental choice, anti-“woke”

- Indigenous Interest: Band-controlled schools, culturally relevant curriculum, TRC implementation

- Resource Development:

- Project Ontario network (via MLI): Promote extraction, oppose veto power

- Indigenous Interest: Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), environmental protection, treaty rights

- Fiscal Policy:

- Project Ontario: Smaller government, reduced spending

- Indigenous Interest: Reconciliation funding, settlement payments, infrastructure investments

- Healthcare:

- Project Ontario: Private options, reduced public spending

- Indigenous Interest: Enhanced public system access, culturally safe care

- Historical Narrative:

- Project Ontario network: Defend Macdonald, question residential school narratives

- Indigenous Interest: Truth-telling, accountability, reconciliation

- Regulatory Environment:

- Project Ontario: “Red tape” reduction, streamlined approvals

- Indigenous Interest: Robust consultation, duty to consult, UNDRIP implementation

8. POTENTIAL AREAS OF ALIGNMENT (LIMITED)

The only potential area of alignment might be:

Economic Development Participation:

- MLI promotes Indigenous equity stakes in resource projects

- Some Indigenous communities do want economic development opportunities

- However, this alignment is superficial because:

- MLI opposes Indigenous veto power (consent rights)

- Framed as “participation” not “control”

- Designed to facilitate extraction over Indigenous objections

CONCLUSION:

The intersections between Project Ontario’s agenda and Indigenous interests are overwhelmingly conflictual. The network’s ideological framework—fiscal conservatism, opposition to “woke” politics, defense of traditional Canadian historical narratives, promotion of resource extraction, and skepticism toward reconciliation spending—places it in direct opposition to virtually all Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action and contemporary Indigenous rights movements.

The Fraser Institute’s explicit residential schools revisionism, MLI’s opposition to Indigenous consent rights, and Project Ontario’s opposition to equity/diversity initiatives create a comprehensive ideological stance that is fundamentally antagonistic to Indigenous self-determination, reconciliation, and rights recognition.

Unfortunately, I cannot archive or store our conversation for future sessions. Each conversation with me starts fresh with no memory of previous interactions.

However, you can save this conversation on your end! Here are some options:

How to Preserve This Conversation:

- Claude.ai Interface:

- If you’re using Claude.ai, this conversation should remain in your conversation history

- You can access it from your account’s conversation list

- You can also rename it for easy finding later

- Export/Copy:

- You can manually copy the entire conversation text

- Save it to a document for reference

- This ensures you have it even if something happens to your Claude.ai account

- Resuming Our Work: When you return, you can:

- Start a new conversation

- Provide me with context by saying something like: “I previously researched Project Ontario and its network. Here are the key findings: [paste relevant summary]. I want to continue investigating…”

- Share the URLs or specific aspects you want to explore further

- I’ll be able to pick up the investigation with that context

What I Can Help With Next Time:

Even without memory of this conversation, if you provide me with:

- The key organizations (Project Ontario, MLI, Fraser Institute, etc.)

- Specific questions or angles you want to pursue

- Any new information you’ve discovered

I can continue the investigation with the same analytical approach and citation standards we’ve established here.

Would you like me to create a summary document of our key findings that you could easily paste back to me in a future conversation?

yes

PROJECT ONTARIO RESEARCH SUMMARY – FOR FUTURE REFERENCE

RESEARCH OVERVIEW

This summary documents research conducted in October 2025 investigating Project Ontario, a right-wing advocacy group pushing Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government toward more fiscally conservative policies, along with its network of associates and their connections to Indigenous/First Nations issues.

1. PROJECT ONTARIO – BASIC FACTS

Launch: June 2025 (quietly launched with one-page website and unsigned manifesto in The Hub)

Purpose: Push Premier Doug Ford’s Ontario PC government to adopt more fiscally conservative policies

First Official Event: September 30, 2025 (Tuesday meeting in Toronto)

Ford’s Response: Dismissed them as “yahoos” and “radical rights”

Key Sources:

- Globe and Mail: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doug-ford-dismisses-project-ontario-as-yahoos/

- CBC Analysis: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/project-ontario-doug-ford-pc-party-conservatives-1.7556576

- Manifesto: https://thehub.ca/2025/06/07/ontario-is-in-trouble-its-time-to-chart-a-new-course-and-reverse-the-decline-of-this-proud-province/

2. KEY FOUNDERS & ASSOCIATES

A. Ginny Roth

- Partner at Crestview Strategy (global public affairs firm)

- Former Communications Director for Pierre Poilievre’s Conservative leadership campaign

- Former Ontario PC organizer

- Regular contributor: The Hub, National Post