https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/residential-school-denialism-explainer-1.7485959

Residential school denialism: what is it and how to recognize it

Denialism is about misrepresenting and minimizing residential school truths, say experts

Residential school denialism does not deny the existence of the school system, but rather downplays, excuses or misrepresents facts about the harms caused by it, experts say.

Earlier this month, B.C. MLA Dallas Brodie was kicked out of the Conservative Party caucus after she made a series of comments questioning Indigenous people’s experiences of residential schools.

In a post on X, Brodie responded by saying she was simply speaking the truth. She has previously told CBC News she refutes claims that she has been engaging in residential school denialism.

However, experts, including historian Sean Carleton, say Brodie’s comments are part of the “predictable” and “rigorously debunked” arguments used frequently by residential school deniers.

“I think it’s important to define what residential school denialism is not, which is the denial of the system’s existence or even that the system had some negative effects. We don’t see a lot of that,” said Carleton, who is also an assistant professor of Indigenous studies at the University of Manitoba.

Instead, he said, denialism is “a strategy to twist, downplay, misrepresent, minimize residential school truths in favour of more controversial opinions that the system was well-intentioned.”

He said denialism in all forms — whether talking about climate change or flat Earth conspiracies — is “an attempt to shake public confidence in something that we have consensus about.”

Sowing doubt

Patterns in behaviour, Carleton said, can help distinguish those who are asking questions in good faith from those who are trying to sow doubt. In Brodie’s case, he said there were multiple instances where her comments failed to address the full reality of residential schools.

“If you call Brodie, for example, a denier, she’ll say, ‘But I’m not denying — this is the truth. The truth is that they haven’t found any bodies yet,’” he said.

“But then when you do the homework and you look at the pattern of what she’s doing … she’s not actually saying, ‘Well, we know that 4,000 children have died in that system [with] 50 confirmed at Kamloops.’”

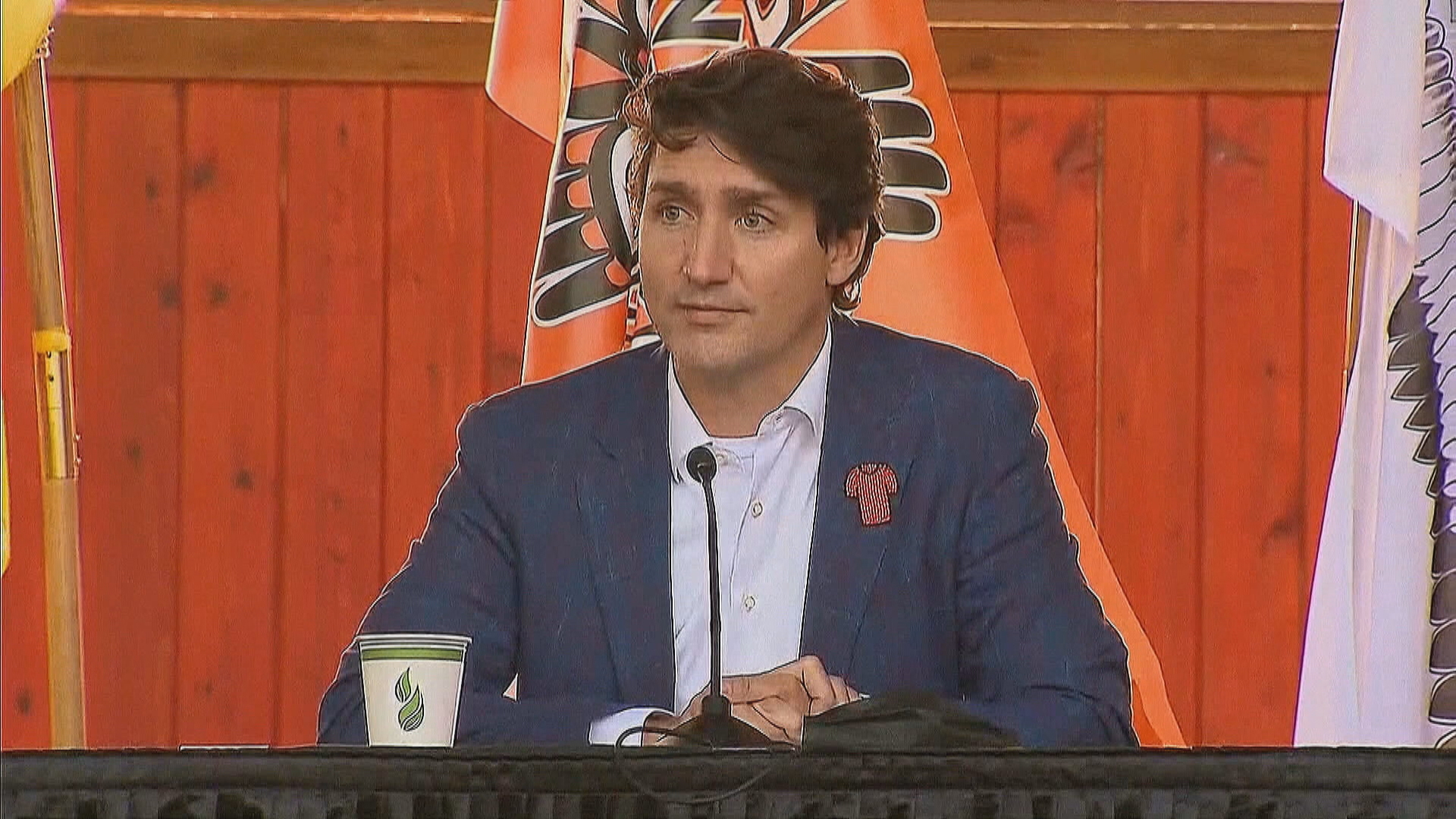

WATCH | How do experts define denialism?

Hear from experts on what residential school denialism is and is not, and why that matters.

Crystal Gail Fraser, who is Gwichyà Gwich’in and an associate professor in history and Native studies at the University of Alberta, said she thinks about residential school denialism in terms of “little grey areas.”

Like Carleton, she thinks it’s important to note denialism is not about saying residential schools never happened.

“[It’s about] denying survivors’ experiences, how they experienced their institutionalization as a child, but also the so-called intent of residential schools,” she said.

Fraser said she sees denialism when people suggest the residential school system had good intentions, as well as when people question the motives of survivors who share their stories.

She said denialism will still exist even after all the facts about residential schools are accepted.

“The ideology of denialism is going to continue beyond residential schools because we still live in a sociopolitical context that justifies colonialism,” she said.

“In order to interrupt the rejection of Indigenous knowledge, whether it’s about residential schools or something else, we will need some kind of a radical transformation in society.”

Discrediting survivors

Ry Moran, founding director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation and associate university librarian – reconciliation at the University of Victoria, said it’s important to him that survivors are centred when thinking about denialism.

Moran, who is Métis, said he defines IRS denialism “as the action or actions that seek to diminish the truths shared by residential school survivors.”

“I think one of the worst goals of denialism is to discredit the truths of residential school survivors,” he said.

Moran worked with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) gathering survivor testimony from thousands of people, and points out that the TRC was just one of several efforts to document the truth about residential schools, alongside the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

“We have an inordinate amount of truth on what occurred inside of the residential schools thanks to all of these collective efforts,” he said.

“[Survivors] have been remarkably consistent in everything that they have said. And time and time again … what we found in the ground, what we found in the archives, or what we found in other sources has verified what they’ve told us.”

Denialism, he said, has been around since the earliest days of the residential school system; kids who ran away and reported abuses were not believed or taken seriously, despite the fact that beatings and abuse were often witnessed by other students, Moran said.

A crime?

Leah Gazan, MP for Winnipeg Centre, tabled a bill in Parliament last year that would have amended the Criminal Code to criminalize residential school denialism.

Gazan’s bill refers to “condoning, denying, downplaying” facts — identical language to the law outlawing Holocaust denial — but adds “justifying the Indian residential school system in Canada or by misrepresenting facts relating to it.”

“Indigenous people have a right to be protected from the incitement of hate like Holocaust denial,” she said.

With an election expected soon, Gazan’s bill is unlikely to move forward. She said if she’s re-elected, she will bring the bill back to Parliament.

,,,,

https://beyond.ubc.ca/8-ways-to-confront-residential-school-denialism/

Truth before reconciliation: 8 ways to identify and confront Residential School denialism

By Dr. Daniel Heath Justice and Dr. Sean Carleton

In its 2015 final report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was clear: “Without truth … there can be no genuine reconciliation.” The problem, the commissioners explained, is that “too many Canadians know little or nothing about the deep historical roots” of the ongoing issues stemming from settler colonialism generally and residential schooling specifically.

Embracing truth is all the more difficult for some because many Canadians still associate residential schooling with the positive images church and state officials used to propagandize and promote these institutions as humanitarian projects.

Such “positive” framings of residential schools justify ongoing colonial policy approaches that continue to harm Indigenous Peoples today.

Rejection, misrepresentation of basic facts

But lack of accurate historical knowledge is not the only barrier to truth and genuine reconciliation. There are a handful of figures — former senator Lynn Beyak, Conservative Party Leader Erin O’Toole, Conrad Black and others — who have openly engaged in denialism.

Residential school denialism is not the outright denial of the Indian Residential School (IRS) system’s existence, but rather the rejection or misrepresentation of basic facts about residential schooling to undermine truth and reconciliation efforts.

Residential school denialists employ an array of rhetorical arguments. The end game of denialism is to obscure truth about Canada’s IRS system in ways that ultimately protect the status quo as well as guilty parties.

Residential school denialists begin and end with a firm belief in innate Indigenous deficiency and settler innocence, often rooted in Christian triumphalism. Their ranks include missionary apologists, writers and academics, right-wing and anti-Indigenous editorialists and relatives of residential school staff who uncritically refer to personal memory and work to defend their family reputations. These are neither informed nor objective commentators.

Avoiding truth, rushing reconciliation

Murray Sinclair, the TRC’s chair, has recently argued that residential school denialism is on the rise and real reconciliation is at risk.

Canada, Sinclair suggests, is rushing reconciliation and leaving the truth behind. In light of recent announcements of unmarked children’s graves across the country, now is the time to confront the truth about Canada’s IRS system and, in the process, disprove and discredit denialism.

The following glossary is the start of an inventory of some common contortions used by denialists to try to undermine the overwhelming documentary and testimonial evidence of widespread, multigenerational, systemic and ongoing violence of the IRS system.

1. Genocide: The destruction, in whole or in part, of a nation or an ethnic group. In spite of the United Nation’s expansive official definition, denialists strategically narrow the term “genocide” to ethnic cleansing events modelled on the Holocaust. Contrary to historical evidence, denialists contend that genocide is not applicable to Canada.

The TRC’s final report shows how Canada’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples fits the definition of genocide, specifically explaining how the residential school system was a form of “cultural genocide.” Some denialists jump on this categorization to suggest that “cultural” genocide is not genocide. That is incorrect. The Canadian Historical Association has recently clarified that genocide is, in fact, the correct term to be using in the Canadian context.

2. School: A place where children are taught a variety of academic subjects. Physical assault, sorting of children according to racist assumptions and on the basis of ability and class have long histories in Canadian education. But the particular combination of factors distinguish residential schools from comparative schooling contexts. These factors include: racist assimilationism; cultural shaming and sexual violence combined with multi-generational collusion of church and state; the explicit aim of isolating children to neutralize community resistance to government control.

Denialists often make false comparisons between boarding schools and the violent carceral institutions known as “residential schools.” Canadian policy meant that for more than 100 years and multiple generations, Indigenous children were removed from their families and cultures to institutions where many were abused, malnourished, trafficked to local white families and inflicted with substandard education focused on manual labour and servitude — while government also systemically dispossessed Indigenous lands and resources.

3. “But they learned new skills”: Given little meaningful academic or effective vocational instruction, “new skills” taught in residential institutions included religious indoctrination enforced by corporal punishment and myriad forms of abuse, cultural and bodily shame, alienation from family, disconnection from subsistence economies and substandard orientation for wage labour.

Church and state officials often justify this “education” in humanitarian — even sacred — terms. But all of these “skills” directly supported the destruction of Indigenous ways of life and the ostensible training of children and youth for lower-class “productive” service positions. Indigenous children were not put on vocational or professional paths towards economic or social competition in Canada’s capitalist settler society.

4. “They had good intentions”: No matter how many bodies are found, how many people testify to the lifelong traumas of extensive abuse at the hands of church officials and teachers, denialists evoke the “good intentions” of some school officials as justification for their maintenance of a genocidal school system for over a century.

5. “You’re ignoring all the good things”: Anything at all that made life bearable under a dominant violent context of staff-inflicted cruelties, deprivations and separations from friends, family and home is cited by denialists as a “good” of residential schooling to absolve churches of culpability. Denialists insist on focusing on a minority of individualized, positive recollections from the schools as part of a strategy to discredit those who draw attention to the overall, systemic genocidal effects of the IRS system. Even the Anglican Church of Canada, which ran approximately 30 per cent of residential schools across the country, has clarified that “there was nothing good” about a school system that sought to “kill the Indian in the child.”

6. Balance: An equal weighting of different elements. Denialists often engage in a form of bias known as “false balance” to wrongly suggest that the “good” and the “bad” of residential schooling were equal parts of the “whole story.” The insistence on focusing on “positives” to provide “balance” fundamentally misrepresents the scholarly consensus, supported by overwhelming survivor testimony and backed by historical research, that the overall effects of the system are genocidal.

7. “It was of the times”: The idea that we can’t judge the past by the values of today. This notion wrongly suggests that no one judged the IRS system harshly during its operation. In fact, Indigenous parents, students and community leaders, church employees and even the Department of Indian Affairs’ own medical expert critiqued the system “in their own times.” However, powerful church and state officials chose to downplay and discredit dissent and resistance for over a century to protect the IRS system so that it could continue to support settler colonialism and Canadian nation-building — as a way of protecting their assets and defend against litigation.

8. Civility: What some settlers demand from Indigenous people when their denialism is publicly called out, challenged and discredited. Indigenous anger, sadness and refusal are labelled as uncivil and excluded from so-called mainstream dialogue. By contrast, our public institutions accommodate public settler anger and outrage used to defend denialists.

Overall, residential school denialism is a strategy used to manipulate and undermine the realities of Indigenous Peoples’ painful experiences under Canadian colonialism to protect the status quo. An honest accounting of the past makes possible an honourable future — but only if Canadians have the courage to face it. As the TRC reminds us, we must have truth before reconciliation — anything less will only perpetuate the harms of that history.

If you are an Indian Residential School survivor, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419![]()

Dr. Daniel Heath Justice is a Cherokee Nation citizen and Professor of Critical Indigenous Studies and English at UBC.

Dr. Sean Carleton is an Assistant Professor with the Departments of History and Indigenous Studies at the University of Manitoba.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. To republish this article, please refer to the original article.

https://theconversation.com/truth-before-reconciliation-8-ways-to-identify-and-confront-residential-school-denialism-164692

Truth before reconciliation: 8 ways to identify and confront Residential School denialism

In its 2015 final report, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was clear: “Without truth … there can be no genuine reconciliation.” The problem, the commissioners explained, is that “too many Canadians know little or nothing about the deep historical roots” of the ongoing issues stemming from settler colonialism generally and residential schooling specifically.

Embracing truth is all the more difficult for some because many Canadians still associate residential schooling with the positive images church and state officials used to propagandize and promote these institutions as humanitarian projects.

Such “positive” framings of residential schools justify ongoing colonial policy approaches that continue to harm Indigenous Peoples today.

Rejection, misrepresentation of basic facts

But lack of accurate historical knowledge is not the only barrier to truth and genuine reconciliation. There are a handful of figures — former senator Lynn Beyak, Conservative Party Leader Erin O’Toole, Conrad Black and others — who have openly engaged in denialism.

Residential school denialism is not the outright denial of the Indian Residential School (IRS) system’s existence, but rather the rejection or misrepresentation of basic facts about residential schooling to undermine truth and reconciliation efforts.

Residential school denialists employ an array of rhetorical arguments. The end game of denialism is to obscure truth about Canada’s IRS system in ways that ultimately protect the status quo as well as guilty parties.

Residential school denialists begin and end with a firm belief in innate Indigenous deficiency and settler innocence, often rooted in Christian triumphalism. Their ranks include missionary apologists, writers and academics, right-wing and anti-Indigenous editorialists and relatives of residential school staff who uncritically refer to personal memory and work to defend their family reputations. These are neither informed nor objective commentators.

Avoiding truth, rushing reconciliation

Murray Sinclair, the TRC’s chair, has recently argued that residential school denialism is on the rise and real reconciliation is at risk.

Canada, Sinclair suggests, is rushing reconciliation and leaving the truth behind. In light of recent announcements of unmarked children’s graves across the country, now is the time to confront the truth about Canada’s IRS system and, in the process, disprove and discredit denialism.

The following glossary is the start of an inventory of some common contortions used by denialists to try to undermine the overwhelming documentary and testimonial evidence of widespread, multigenerational, systemic and ongoing violence of the IRS system.

1. Genocide: The destruction, in whole or in part, of a nation or an ethnic group. In spite of the United Nation’s expansive official definition, denialists strategically narrow the term “genocide” to ethnic cleansing events modelled on the Holocaust. Contrary to historical evidence, denialists contend that genocide is not applicable to Canada.

The TRC’s final report shows how Canada’s treatment of Indigenous Peoples fits the definition of genocide, specifically explaining how the residential school system was a form of “cultural genocide.” Some denialists jump on this categorization to suggest that “cultural” genocide is not genocide. That is incorrect. The Canadian Historical Association has recently clarified that genocide is, in fact, the correct term to be using in the Canadian context.

Read more: Canada’s hypocrisy: Recognizing genocide except its own against Indigenous peoples

2. School: A place where children are taught a variety of academic subjects. Physical assault, sorting of children according to racist assumptions and on the basis of ability and class have long histories in Canadian education. But the particular combination of factors distinguish residential schools from comparative schooling contexts. These factors include: racist assimilationism; cultural shaming and sexual violence combined with multi-generational collusion of church and state; the explicit aim of isolating children to neutralize community resistance to government control.

Denialists often make false comparisons between boarding schools and the violent carceral institutions known as “residential schools.” Canadian policy meant that for more than 100 years and multiple generations, Indigenous children were removed from their families and cultures to institutions where many were abused, malnourished, trafficked to local white families and inflicted with substandard education focused on manual labour and servitude — while government also systemically dispossessed Indigenous lands and resources.

3. “But they learned new skills”: Given little meaningful academic or effective vocational instruction, “new skills” taught in residential institutions included religious indoctrination enforced by corporal punishment and myriad forms of abuse, cultural and bodily shame, alienation from family, disconnection from subsistence economies and substandard orientation for wage labour.

Church and state officials often justify this “education” in humanitarian — even sacred — terms. But all of these “skills” directly supported the destruction of Indigenous ways of life and the ostensible training of children and youth for lower-class “productive” service positions. Indigenous children were not put on vocational or professional paths towards economic or social competition in Canada’s capitalist settler society.

4. “They had good intentions”: No matter how many bodies are found, how many people testify to the lifelong traumas of extensive abuse at the hands of church officials and teachers, denialists evoke the “good intentions” of some school officials as justification for their maintenance of a genocidal school system for over a century.

5. “You’re ignoring all the good things”: Anything at all that made life bearable under a dominant violent context of staff-inflicted cruelties, deprivations and separations from friends, family and home is cited by denialists as a “good” of residential schooling to absolve churches of culpability. Denialists insist on focusing on a minority of individualized, positive recollections from the schools as part of a strategy to discredit those who draw attention to the overall, systemic genocidal effects of the IRS system. Even the Anglican Church of Canada, which ran approximately 30 per cent of residential schools across the country, has clarified that “there was nothing good” about a school system that sought to “kill the Indian in the child.”

6. Balance: An equal weighting of different elements. Denialists often engage in a form of bias known as “false balance” to wrongly suggest that the “good” and the “bad” of residential schooling were equal parts of the “whole story.” The insistence on focusing on “positives” to provide “balance” fundamentally misrepresents the scholarly consensus, supported by overwhelming survivor testimony and backed by historical research, that the overall effects of the system are genocidal.

7. “It was of the times”: The idea that we can’t judge the past by the values of today. This notion wrongly suggests that no one judged the IRS system harshly during its operation. In fact, Indigenous parents, students and community leaders, church employees and even the Department of Indian Affairs’ own medical expert critiqued the system “in their own times.” However, powerful church and state officials chose to downplay and discredit dissent and resistance for over a century to protect the IRS system so that it could continue to support settler colonialism and Canadian nation-building — as a way of protecting their assets and defend against litigation.

8. Civility: What some settlers demand from Indigenous people when their denialism is publicly called out, challenged and discredited. Indigenous anger, sadness and refusal are labelled as uncivil and excluded from so-called mainstream dialogue. By contrast, our public institutions accommodate public settler anger and outrage used to defend denialists.

Overall, residential school denialism is a strategy used to manipulate and undermine the realities of Indigenous Peoples’ painful experiences under Canadian colonialism to protect the status quo. An honest accounting of the past makes possible an honourable future — but only if Canadians have the courage to face it. As the TRC reminds us, we must have truth before reconciliation — anything less will only perpetuate the harms of that history.

If you are an Indian Residential School survivor, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419

Facing the Facts: Why Residential School Denialism Must Be Called Out

Facing the Facts: Why Residential School Denialism Must Be Called Out

Content warning: This post contain information about residential schools. Mental health support is available.

In February 2025, a troubling story out of British Columbia made headlines and reignited a painful conversation.

Dallas Brodie, a former Member of the Legislative Assembly of the BC Conservative Party, publicly supported lawyer James Heller, who had filed a legal challenge against a mandatory cultural competency course for lawyers in the province. The course includes education about residential schools and the findings at the former Kamloops Residential School site.

Heller’s objection? He claimed the Law Society of BC was misleading the public by not emphasizing the word “potential” when describing the 215 unmarked graves detected through ground-penetrating radar in Kamloops. Brodie doubled down on this rhetoric, stating that the number of “confirmed child burials” at Kamloops was zero, despite the fact that the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation had already confirmed the findings based on both technology and community knowledge.

These remarks were quickly and widely condemned.

An Act of “Racist Residential School Denialism”

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs called Brodie’s comments an act of “racist residential school denialism,” and demanded a public apology to Survivors. Indigenous leaders and organizations emphasized that this kind of language, framing the findings as speculative, ultimately ignores the oral histories and lived experiences of Indigenous people.

Just days later, Brodie was expelled from the Conservative caucus.

What is Residential School Denialism and Why is it a Concern?

Residential school denialism doesn’t always come in the form of outright rejection of history. More often, it shows up as doubt, deflection, and demands for more “proof”—even in the face of well-documented truth.

It’s not just offensive. It’s dangerous.

Denying, minimizing, or reframing the violence and deaths that took place in residential schools retraumatizes Survivors, undermines truth-telling, and halts progress toward reconciliation.

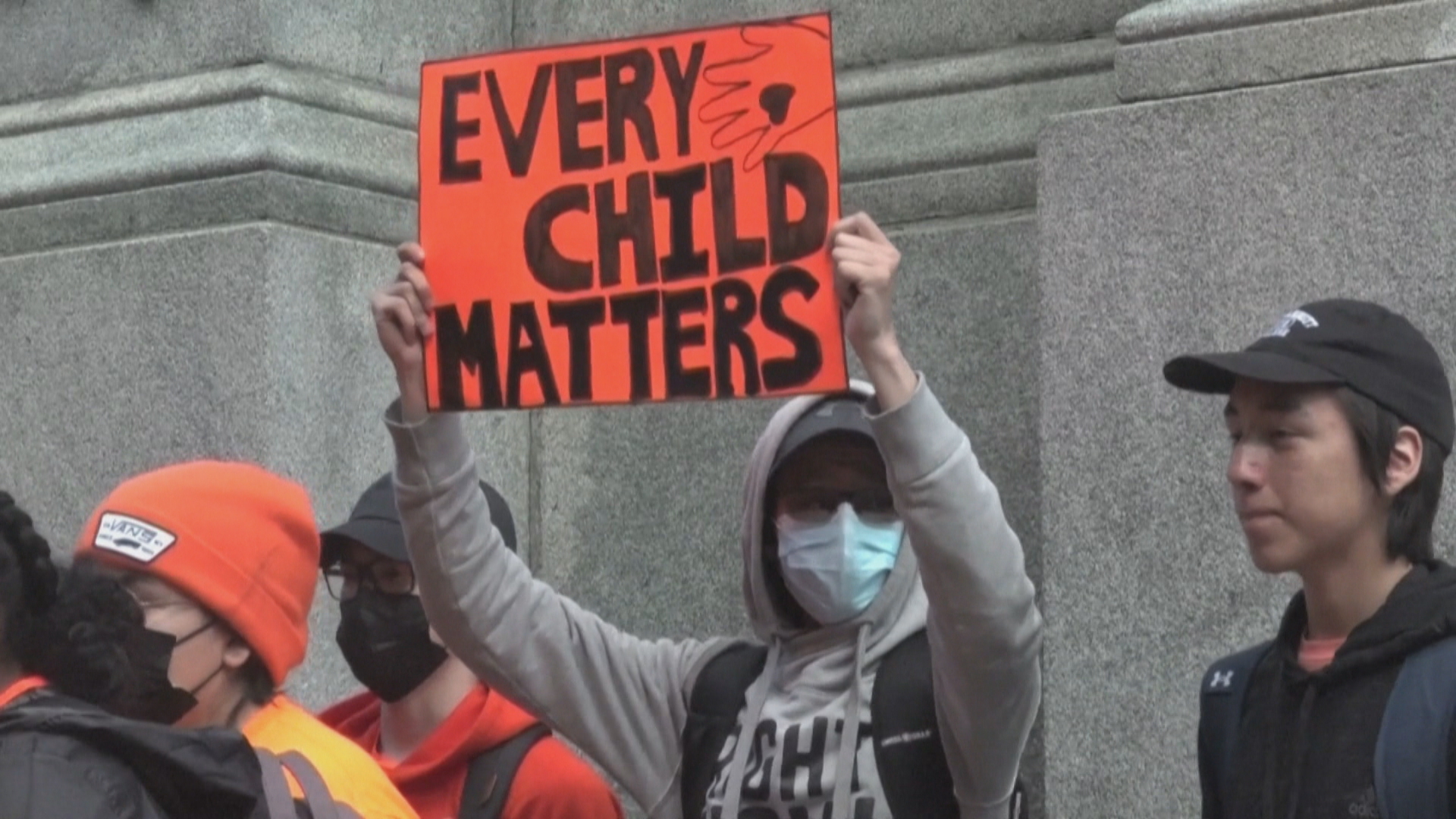

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) made clear that more than 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed in residential schools—many never returned home. The TRC documented thousands of deaths and stated that the true number is likely much higher.

Since 2021, Indigenous communities across the country have been leading investigations at former residential school sites, using ground-penetrating radar to locate unmarked graves. These are not discoveries—they are confirmations of what Survivors and families have been telling us for generations.

Language Matters

When people like Heller and Brodie question whether the graves in Kamloops are “confirmed,” they’re not just scrutinizing a word. They’re casting doubt on the lived truth of Survivors.

The word “recovery” is used intentionally by many Indigenous communities. Not because the children were lost, but because they were taken. These are not new truths—they are truths that have finally been acknowledged by wider Canada. Words like “discovery” or “alleged” erase that.

What We Can Do

If you’re reading this, you likely care deeply about truth, justice, and reconciliation. So, what can we do when denialism shows up?

- Call it out. When you see misinformation, whether in the news, online, or in conversation, correct it. Share verified facts and Indigenous-led sources.

- Centre Survivors. Trust the stories of those who lived through residential schools. Share and uplift their voices.

- Support Indigenous-led search and memorial efforts. Many communities are fundraising for ground searches, ceremonies, and healing.

- Educate yourself and others. Recommended reading below:

Truth Before Reconciliation

The 215+ Pledge exists to honour the children who never came home, and to call people into action—not just for a moment, but for the long haul.

The events of the past few months are a stark reminder that the truth is still under attack. And that’s why this work remains urgent.

Take the 215+ Pledge. Stand up to denialism and be a part of truth-telling.

Resources:

Residential School History – NCTR

About the Author

Quinn Roffey- Antoine is Plains Cree from Poundmaker Cree Nation in Treaty 6 Territory. She grew up in Toronto, Ontario and resides there now.

,,,

https://www.bcafn.ca/news/fnlc-calls-canada-prioritize-legislation-create-legal-protections-against-residential-school

FNLC Calls on Canada to Prioritize Legislation to Create Legal Protections against Residential School Denialism

- Press Release

March 20, 2025

(xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh)/Vancouver, B.C.) The First Nations Leadership Council (FNLC) is deeply concerned by the rise of Residential School denialism in the province, particularly the egregious misuse of public office by elected officials using their platforms to sow public doubt and promote misinformation and anti-Indigenous racism. The FNLC calls for the government of Canada to prioritize implementation of federal legislation to protect against Residential School denialism, as has been done with Bill C-19 which criminalized Holocaust denialism in Canada.

First Nations leadership across B.C. have passed resolutions at the B.C. Assembly of First Nations and the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs calling for the rights and testimony of survivors to be upheld, implementation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, rejection and criminalization of Residential School denialism, and denouncing recent comments made by then-Conservative MLA Dallas Brodie regarding unmarked graves and burial sites at the Kamloops Indian Residential School (UBCIC Resolution 2024-33; BCAFN #02/2025) A similar resolution will go forward to the next First Nations Summit meeting in April.

We commend MP Leah Gazan for introducing the Private Member’s Bill C-413 An Act to amend the Criminal Code (promotion of hatred against Indigenous peoples), which aimed to criminalize Residential School denialism, and hold individuals accountable for spreading hateful speech and misinformation about the Residential School system and Indigenous people. We feel strongly that legislation is needed to combat misinformation, denialism, and racism promoted by elected officials and hate groups. We urge the government of Canada to uphold its obligations under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the principles of reconciliation, and urge all members of Parliament to work across party lines to make it an offence to promote hatred against Indigenous peoples by condoning, denying, downplaying, or justifying Residential Schools in Canada or misrepresenting related facts.

“The language and actions of publicly elected officials significantly shape societal attitudes, influence public perceptions, and have the power to either foster understanding and healing or perpetuate division In her statements, MLA Brodie showed blatant disrespect for her position in public office by promoting harmful Residential School denialism on her social media. We are glad Mr. Rustad has removed MLA Brodie from the Conservative Party and believe that she is unfit to sit as an MLA in the legislature. It is essential that the governments of BC and Canada take a strong stance against Residential School denialism, by rightfully recognizing this harmful rhetoric as hate speech. Political leaders must acknowledge the gravity of traumas endured by Indigenous peoples at these institutions and must engage with First Nations and respectfully honour the stories of survivors. As a society we must foster dialogue that supports reconciliation, as all political leaders in BC work to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” stated B.C Assembly of First Nations Regional Chief, Terry Teegee.

“Residential School denialists try to hide facts from the public. They intentionally fail to acknowledge or mention the dozens of people convicted of, or who have pled guilty to, sexually and/or physically assaulting First Nations children in Residential Schools. They also neglect to speak about the thousands of abusers located by multiple private investigation firms contracted by the Federal Government,” said Hugh Braker of the First Nations Summit Political Executive. “These denialists purposely reject the words of the BC Supreme Court Judge, who at the sentencing of offender Henry Plint to 11 years in prison, stated that Residential Schools were ‘…factories for child abuse’ and that ‘the Federal Government has admitted that up to 6,000 Indian Residential School children died in Residential School.’” “Denying or ignoring the truth about one of the most horrendous parts of Canada’s history is an obstacle to reconciliation and does nothing except cause residential school survivors’ additional pain and suffering,” Braker concluded.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, UBCIC President concluded, “Indigenous peoples have been combating racism and suppression of our knowledge from the highest levels of government since the establishment of Canada, so it comes as no surprise that denialist views which aim to minimize the harms of Residential Schools and intentionally mislead and embolden the public against us endure within our public institutions. Residential School denialism is not about academic debate or questioning history in good faith, it is an ugly and thinly veiled attempt to sow doubt, belittle the experiences of survivors, and distort our shared knowledge from survivors and archival and archaeological research which detail the profound intergenerational harms of these institutions. I implore the current, and any subsequent government of Canada, to take bold legislative action to protect against the spread of dangerous anti-Indigenous racism and denialist rhetoric in equal measure to Holocaust denialism protections. We need only look to our southern neighbours to see the harrowing impacts of leaving hate unchecked.”

https://libguides.uvic.ca/residentialschooldenialism/today

resistance to addressing the legacies of colonialism. Carmen Celestini, a lecturer at the University of Waterloo who studies far-right movements, notes that denialism has evolved over the past year, moving from fringe conspiracy circles to becoming a central talking point among white Christian nationalists. According to Celestini, these groups often frame discussions about residential schools as an attempt to “oppress white people and make white people feel guilt.” She adds that denialism frequently stems from a sense of alienation, particularly among predominantly white men.

resistance to addressing the legacies of colonialism. Carmen Celestini, a lecturer at the University of Waterloo who studies far-right movements, notes that denialism has evolved over the past year, moving from fringe conspiracy circles to becoming a central talking point among white Christian nationalists. According to Celestini, these groups often frame discussions about residential schools as an attempt to “oppress white people and make white people feel guilt.” She adds that denialism frequently stems from a sense of alienation, particularly among predominantly white men.

Leave a Reply